Quick Facts

| Fact | Detail |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Wystan Hugh Auden |

| Date of Birth | February 21, 1907 |

| Place of Birth | York, England |

| Date of Death | September 29, 1973 |

| Place of Death | Vienna, Austria |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Citizenship | United Kingdom; United States (from 1946) |

| Education | Christ Church, Oxford (MA) |

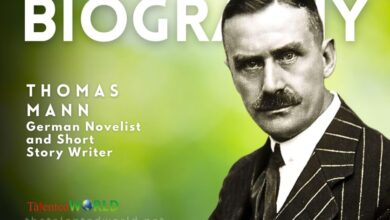

| Spouse | Erika Mann (married 1935, of convenience) |

| Notable Works | “Funeral Blues”, “September 1, 1939”, “The Shield of Achilles”, “The Age of Anxiety”, “For the Time Being”, “Horae Canonicae” |

| Career Highlights | – Wide public attention with his first book of poems, Poems, in 1930 |

| – Won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for The Age of Anxiety in 1947 | |

| – Professor of Poetry at Oxford from 1956 to 1961 | |

| – Highly prolific writer of prose essays and reviews on literary, political, psychological, and religious subjects | |

| – Controversial and influential figure, with critical views ranging from sharply dismissive to strongly affirmative | |

| Posthumous Impact | – His poems became known to a wider public through films, broadcasts, and popular media |

W. H. Auden Books

| Title | Year |

|---|---|

| Funeral Blues | 1938 |

| The Unknown Citizen | 1940 |

| Poems | 1930 |

| September 1, 1939 | 1939 |

| The Age of Anxiety | 1947 |

| The Shield of Achilles | 1952 |

| Look, Stranger! | 1936 |

| Wh Auden Poems | 1928 |

| Another Time | 1940 |

| Tell Me the Truth about Love: Fifteen Poems | – |

| For the Time Being | 1966 |

| Spain | – |

| The Sea and the Mirror | – |

| The Dyer’s Hand | 1962 |

| The Double Man | 1941 |

| Letters from Iceland | 1937 |

| Journey to a War | 1939 |

| The Orators | 1932 |

| Lectures on Shakespeare | – |

| Poetry of W. H. Auden | 1979 |

| Poems (1930) | 1933 |

| Homage to Clio | 1960 |

| Collected Poems | – |

| Thirties Poets: (Louis MacNeice, W. H. Auden, Cecil Day-Lewis, Stephen Spender) | – |

| The Complete Works of W. H. Auden: Prose, Volume III, 1949-1955 | 2007 |

| City Without Walls | 1969 |

| A Certain World | 1970 |

| The Age of Anxiety: A Baroque Eclogue | 1947 |

| The Complete Works of W.H. Auden: 1963-1968 | 2015 |

| Thank You, Fog | 1974 |

| About the House | 1965 |

| The Complete Works of W.H. Auden: 1969-1973 | 2015 |

| Nones | 1951 |

| The Complete Works of W. H. Auden: Poems, Volume I: 1927–1939 | – |

| Collected Shorter Poems, 1927-1957 | 1962 |

| Academic Graffiti | 1971 |

| Auden: Poems: Edited by Edward Mendelson | – |

| W.H. Auden | 1954 |

| Secondary Worlds | 1968 |

| The English Auden | – |

| Portable Poets of the English Language, Elizabethan: 2vo | 1950 |

| Van Gogh: A Self Portrait, Letters Revealing His Life as a Painter | – |

| The Ascent of F.6 and On the Frontier | 1958 |

| The old man’s road | 1956 |

| Collected Poems [1991] | – |