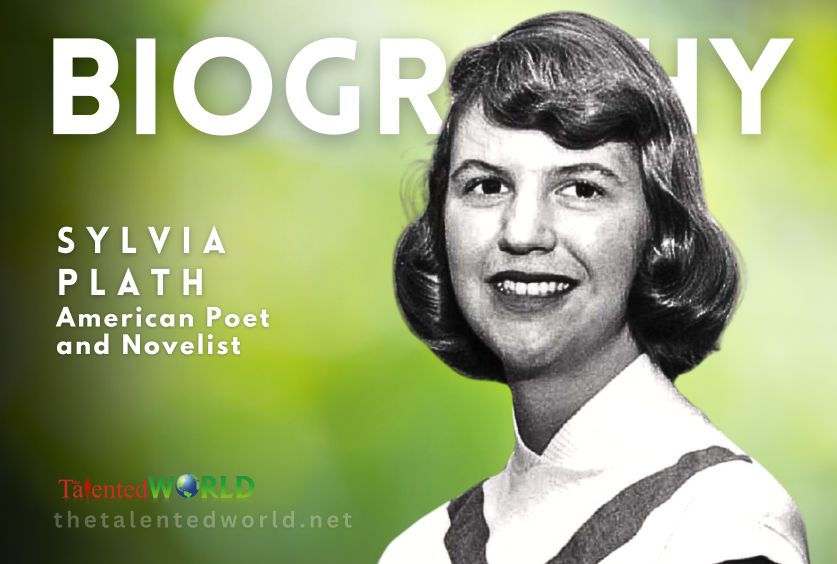

| Full Name | Sylvia Plath |

| Date of Birth | October 27, 1932 |

| Date of Death | February 11, 1963 |

| Age | 30 |

| Place of Birth | Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Place of Death | London, England |

| Resting Place | Heptonstall Church, England |

| Pen Name | Victoria Lucas |

| Occupation | Poet, novelist, short story writer |

| Education | Smith College (BA), Newnham College, Cambridge, Boston University |

| Period | 1960–1963 |

| Genre | Poetry, fiction, short story |

| Literary Movement | Confessional poetry |

| Notable Works | The Colossus and Other Poems (1960), Ariel (1965), The Bell Jar |

| Notable Awards | Fulbright Scholarship, Glascock Prize, Pulitzer Prize for Poetry (posthumously) |

| Spouse | Ted Hughes (m. 1956) |

| Children | Frieda Hughes, Nicholas Hughes |

| Parents | Otto Plath (father), Aurelia Schober (mother) |

| Notable Contributions | Advancing the genre of confessional poetry, Pulitzer Prize for Poetry (posthumously) for The Collected Poems |

| Notable Traits | Clinically depressed for most of her adult life, treated with early versions of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), tumultuous relationship with Ted Hughes |

| Notable Works (posthumous) | The Bell Jar, Ariel, The Collected Poems |