Jacqueline Fernandez’s Mumbai Residence Engulfed in Fire: No Injuries Reported!

-

Entertainment

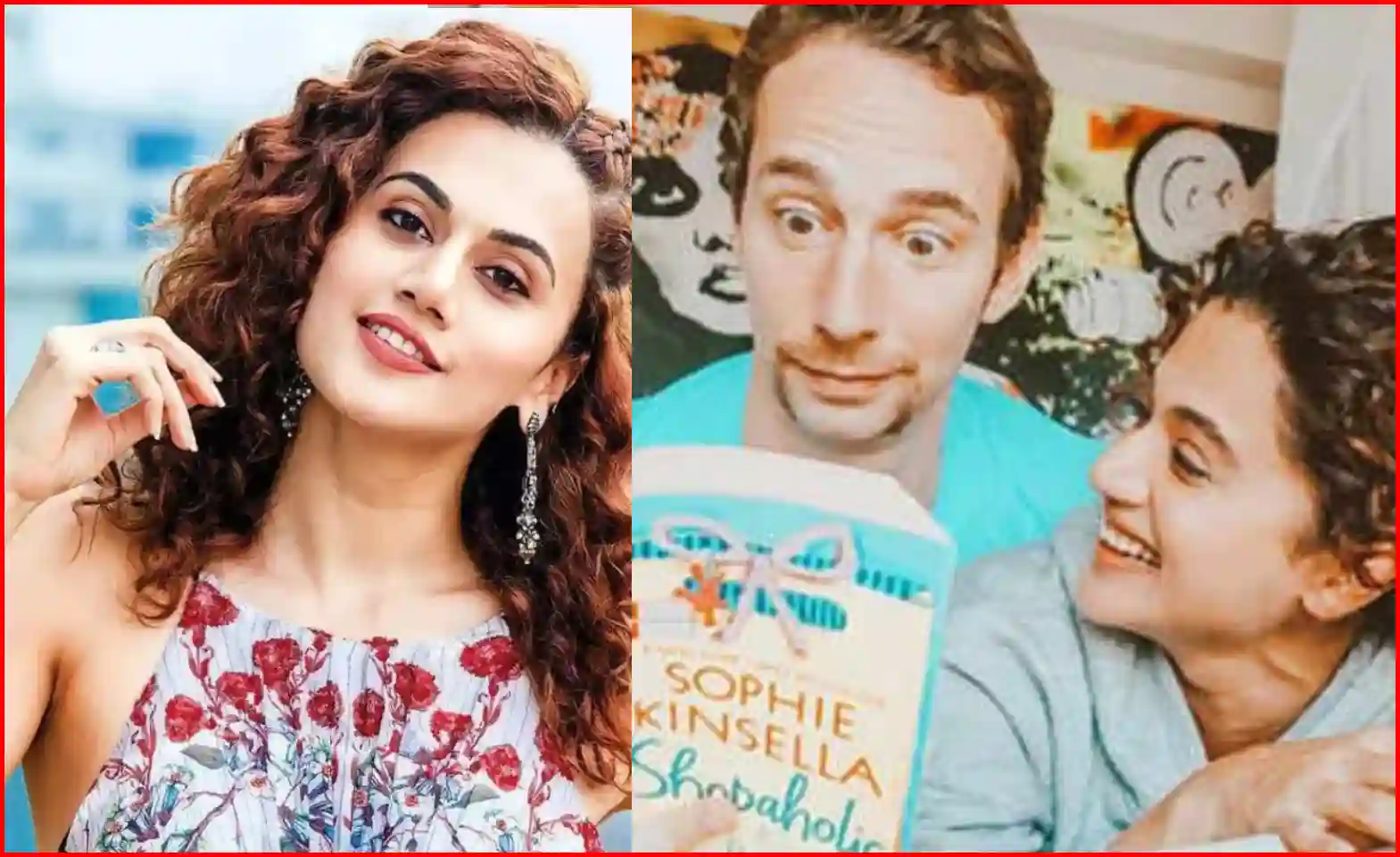

Indian actress Rakul Preet and Jackie Bhagnani’s first glimpse after their wedding

The first picture after the wedding of famous Bollywood actor Jackie Bhagnani and actress Rakul Preet Singh is out. According…

Read More » -

-

-

-

-

Politics

Princess Sheikha Mehra and Sheikh Mana are expected to have a baby girl.

Princess Sheikha Mehra Al Maktoum, daughter of the Vice President and Prime Minister of the United Arab Emirates, Sheikh Mohammed…

Read More » -

-

-

-

-

Sports

Navigating Grief and Resilience: Rebecca Adlington’s Courageous Journey

In a heartbreaking revelation, former Olympic swimmer Rebecca Adlington recently shared the devastating news of the loss ....

Read More » -

-

-

-

-

Technology

Famous personalities are expected to attend the wedding of Mukesh Ambani’s younger son

The list of guests attending the pre-wedding celebrations of Indian businessman Mukesh Ambani’s younger sons Anant Ambani and Radhika Merchant…

Read More » -

-

-

-

Famous Youtubers

Lilly Singh

Biography Lilly Singh, who was born in Toronto, Canada on September 26,…

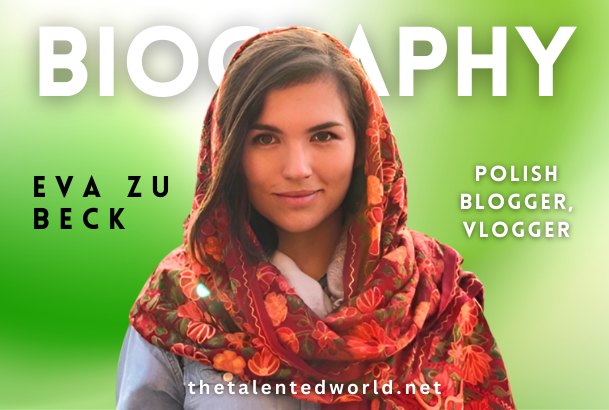

Eva Zu Beck

Biography Take a virtual journey with us as we explore the fascinating…

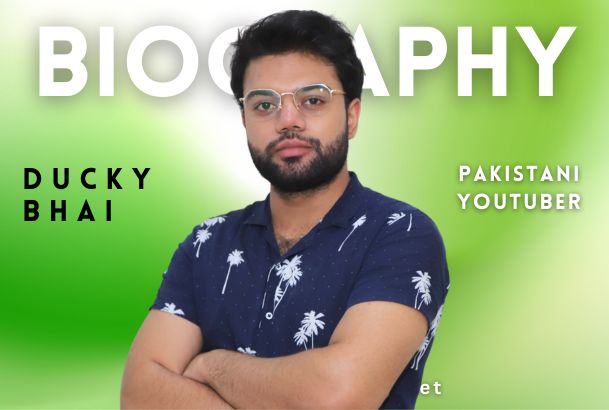

Ducky Bhai

Biography: Ducky Bhai, also known as Saad ur Rehman, is a notable…

Azad Chaiwala

Biography: Azad Chaiwala, a prominent figure in the world of entrepreneurship, YouTube,…

Isabel Paige

Explore the intriguing journey of Isabel Paige net worth, delving into her…

MrBeast

Biography One name sticks out among the rest in the wide world…

Videos

Exclusive Videos

1 / 5 Videos1

Salaar 2: Filming Begins! Latest Updates and Exciting Details | #showbiz #hollywood #tamil #telugu

03:282

#princess Sheikha Mehra and Sheikh Mana Expecting Their First Child! | #showbiz #dubai

03:283

Why did Kiara Advani marry Sidharth at her career's peak? | #showbiz #hollywood #bollywood

03:484

Ranbir Kapoor's Reaction to the Monstrous Machine Gun | #showbiz #hollywood #bollywood #biography

03:595

Top 10 Sci-Fi #movies of the 21st Century | TheTalentedWorld | #showbiz #hollywood #biography

06:01Talented World

Aitzaz Hasan | Complete Biography

Aitzaz Hasan Bangash[a] (1998/1999 – 6 January 2014) was a student from Pakistan who died on 6 January 2014 while…

Matayoshi Mitsuo | Japan’s Crazy Christ!

Mitsuo Matayoshi was a Japanese political activist known for his perennial candidacy. He was the leader and founder .......

Michel Lotito | Man who can eat everything

Michel Lotito began eating unusual material at 9 years of age, and he performed publicly beginning in 1966.....

Yoshiro Nakamatsu | Hold the world record for 3,200 inventions

Yoshiro Nakamatsu is a Japanese inventor. He regularly appears on Japanese talk shows demonstrating his inventions......

Mehran Karimi Nasseri | Lives at the Airport since 1988

Mehran Karimi Nasseri, also known as Sir, Alfred Mehran, was an Iranian refugee who lived in the departure lounge of Terminal 1 in Charles .....

Lal Bihari | The man who fought for 19 years to prove that he is alive.

Lal Bihari Mritak is an Indian farmer and activist from Amilo, in Azamgarh district, Uttar Pradesh, who was officially declared......

Ngoc – Three decades without sleep

Thai Ngoc or Hai Ngoc is an insomniac from Vietnam . According to Vietnamese news outlet Thanh Nien........

Cathie Jung | World’s smallest waist | Height, Weight, Bio & Family

Cathie Jung, holder of the Guinness World Record for the world's smallest waist since 1999. Learn about her dedication to…

-

Academia

Pervez Hoodbhoy

In this article, we talk about famous Pakistani nuclear physicist Pervez Hoodbhoy biography, net worth, age, family, education, pics &…

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Activist

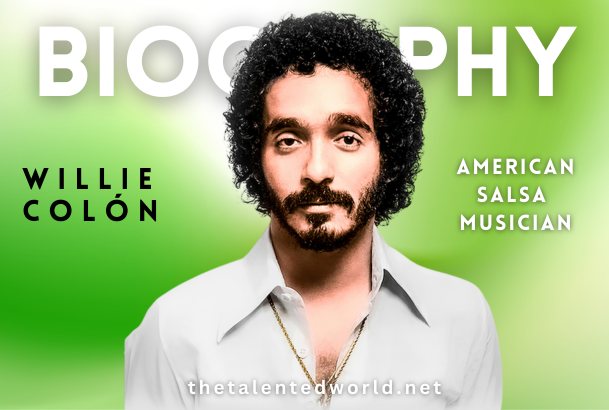

Willie Colon

Biography Willie Colon is a famous American Salsa Musician Producer, & Social Activist. He was born on April 28, 1950,…

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

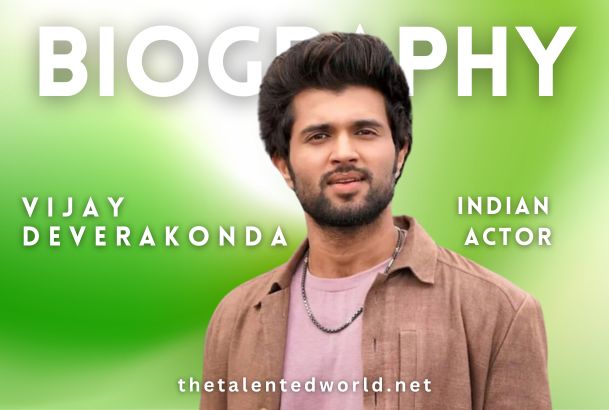

Actors

Vijay Deverakonda

Introduction: Vijay Deverakonda, born in Hyderabad, India on May 9, 1989, is more than simply a name in the Indian…

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Businessman

Elon Musk

Biography Few names in the realm of current business legends ring as loudly as Elon Musk’s. Musk was born on…

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

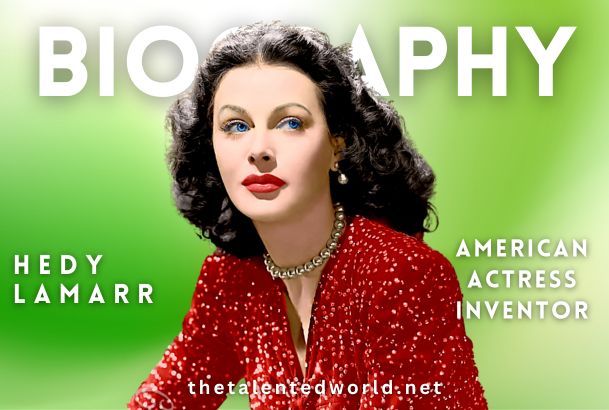

Actress

Hedy Lamarr

Biography Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler, born on November 9, 1914, was an extraordinary Austro-Hungarian-born American actress and pioneering technology developer.…

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Leaders

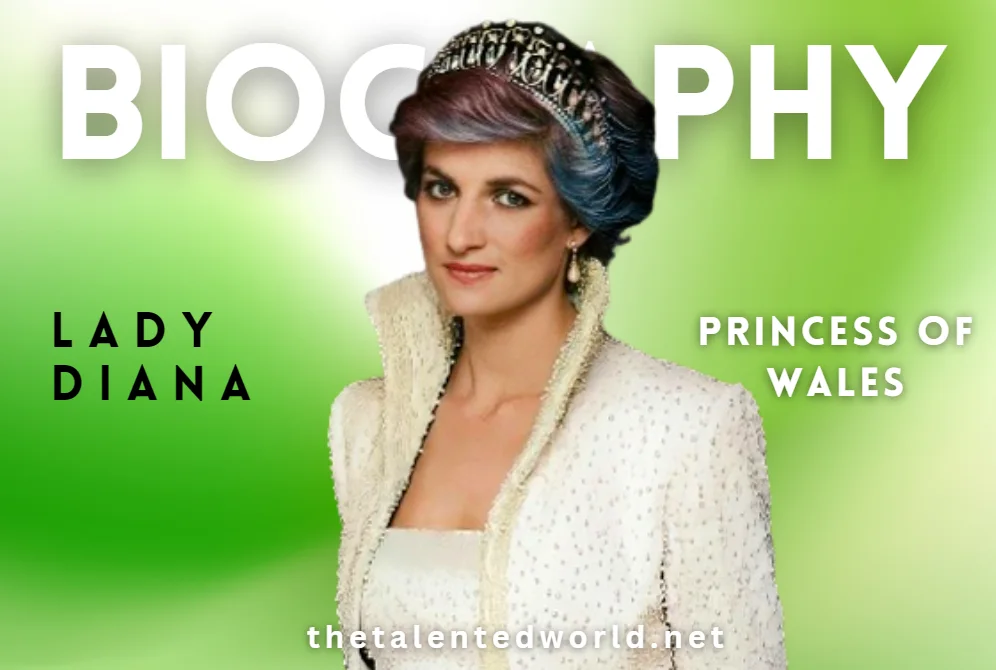

Lady Diana

Biography: Lady Diana, born Diana Frances Spencer on July 1, 1961, left an indelible mark on the world as a…

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Activist

Faiza Khan

Biography Faiza Khan is a famous Pakistani Activist, curator, and visual artist. She was born in August 1975 in Abbottabad.…

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Scientists

Galileo Galilei

Galileo Galilei was an astronomer, engineer, physicist & sometimes escribed as a polymath, from Pisa. His full .......

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

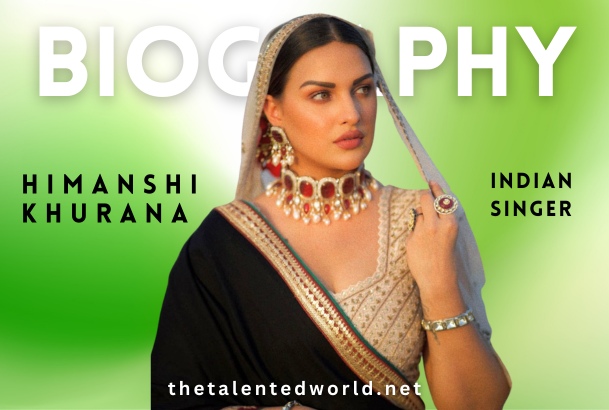

Singers

Garry Sandhu

Biography Garry Sandhu is a famous Indian singer rapper and songwriter. He was born on the fourth of April 1984…

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-